The US Federal Reserve has cut its main interest rate for the first time in ten years, but will it have a knock-on effect?

Source: US Federal Reserve

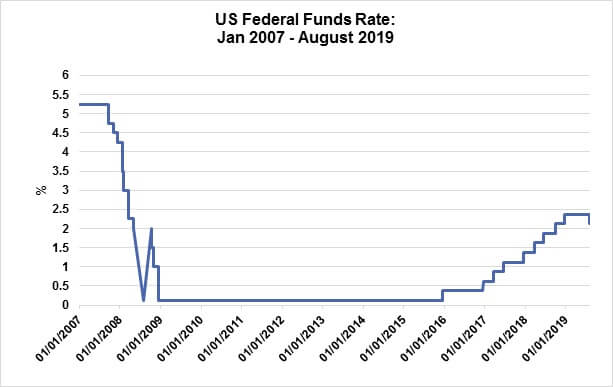

The last time the US central bank, the Federal Reserve, cut its main interest rate was in December 2008, in response to the fallout from the financial crisis. That last drop was preceded by nine interest rate cuts since September of the previous year.

The final 2008 cut, ten days before Christmas, took the Federal Funds rate down from 1.00% to a range of 0.00-0.25%. As the straight line on the graph shows, the rate remained there, just above zero, for the next seven years. It was subsequently gradually nudged up, a quarter of a per cent at a time, reaching 2.25%–2.50% last December.

The new 0.25% cut announced from the beginning of August was widely anticipated, although there were some investors who had forecast a 0.50% reduction. The backdrop to this cut, however, is very different from that of December 2008. Now the US economy is close to full employment and, while growth did cool in the second quarter, it is still running year-on-year at 2.3%. In other times, such conditions would not prompt a rate cut. The central bank is acting now because it wants to prevent the economy slowing any further, at the end of an unusually long period of growth.

On this side of the Atlantic, the European Central Bank has hinted that it could cut interest rates soon. Although the bank took no action in July, it did change its meeting statement to say that it “expects the key ECB interest rates to remain at their present or lower [our italics] levels at least through the first half of 2020”.

The Bank of England’s next interest rate move remains unclear after maintaining the current rate again for August. The various Brexit scenarios could see rates increased to protect a falling pound or as a gradual return to ‘normality; or rates could be cut to stimulate the economy.

‘Lower for longer’ has been a description of the path of interest rates since 2008. It is now beginning to become ‘lower for ever’. Make sure that if you have cash on deposit beyond a rainy-day reserve, you have a good reason for doing so.

The value of your investment can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount you invested. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Investing in shares should be regarded as a long-term investment and should fit in with your overall attitude to risk and financial circumstances.

Content correct at time of writing and is intended for general information only and should not be construed as advice.